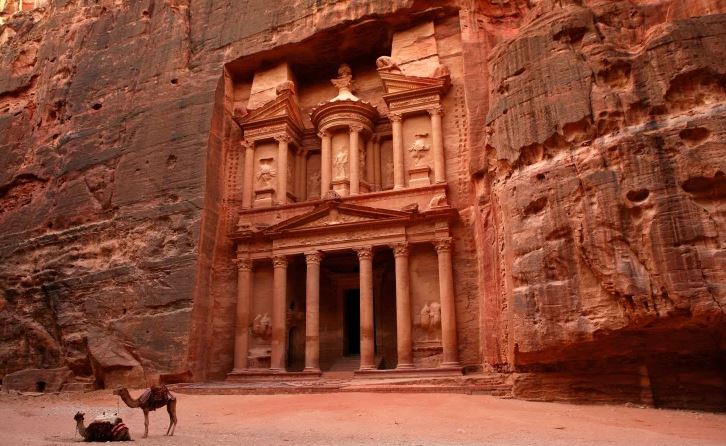

Petra, the ‘rose red city, half as old as time’, located in modern day Jordan, is undoubtedly one of the most dramatic archaeological sites of the world. In a recently conducted Internet poll, it was voted by internet users as one of the ‘seven wonders of the modern world’. In this abandoned city, which lies hidden behind impenetrable mountains and gorges, magnificent rock-cut temples and palaces have been carved into towering cliffs of red and orange sandstone.

The most famous of these structures is the ‘Al Khasneh’ (or the ‘Treasury’), which was made famous in an Indiana Jones film.

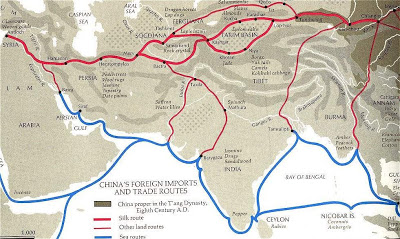

Historians tell us that sometime during the 6th – 4th centuries BC, the Nabataeans, a nomadic tribe from north-western Arabia, entered the region of Petra, and established their cultural, commercial and ceremonial center at Petra. Petra was located strategically at the intersection of the overland Silk Route which connected India and China with Egypt and the Hellenistic world, and the Incense Route from Arabia to Damascus. It soon developed into a thriving commercial center. Sometime during the 3rd century BC, the Nabataeans began to decorate their capital city with splendid rock-cut temples and buildings. Their economic prosperity and architectural achievements continued unabated even after they came under the control of the Roman Empire in 106 CE. The neglect and decline of Petra started soon after Emperor Constantine declared Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire in 324 CE. A series of earthquakes crippled the region in the 7th – 8th centuries and Petra disappeared from the map of the known world, only to be rediscovered centuries later in 1812, by a Swiss explorer named Johann Burckhardt.

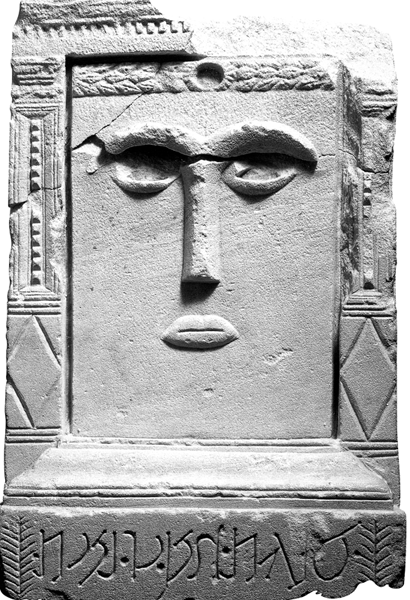

While the architectural grandeur of Petra continues to captivate us, the mysterious religious beliefs of the Nabataeans have puzzled historians. Within the temple of Al Deir, the largest and most imposing rock-cut temple in Petra, is present an unworked, black, block of stone, like an obelisk, representing the most important deity of the Nabataeans – Dushara. The term Dushara means ‘Lord of the Shara’, which refers to the Shara mountains to the north of Petra.

The symbolic animal of Dushara was a bull. All over Petra, Dushara was represented symbolically by stone blocks. In addition, at religious sites throughout the city, the Nabataeans carved a standing stone block called a baetyl, literally meaning ‘house of god’. A baetyl physically marked a deity’s presence. It could be a square or rounded like a dome. Some baetyls’ were depicted with a lunar crescent on the top.

The Nabataeans also appear to be snake worshippers. One of the most prominent structures in Petra is the snake monument, which shows a gigantic coiled-up snake on a block of stone.

Petra Snake Monument. Source: Nabataea.net

1) Baetyl with lunar crescent on top. 2)Dome-shaped Baetyl.

This unusual array of symbolic elements associated with the chief god of the Nabataeans, Dushara, may have confounded historians, but to anyone familiar with the symbolism of the Vedic deity Shiva, the similarities between Dushara and Shiva will be palpable.

Shiva is still worshipped all over India in the form of a black block of stone known as a Shiva Linga. A Shiva Linga, which is essentially a ‘mark’ or ‘symbol’ of Shiva, sometimes appears as an unworked block of stone, much like the idol of Dushara in the temple of Al Deir; but typically it is represented by a smooth, rounded stone which resembles some of the rounded ,dome-shaped, baetyls that we find in Petra.

Shiva is also associated with the mountains; his residence is supposed to be in the Kailash Mountain in the Himalayas, to the north of India, where he spends most of his time engaged in rigorous asceticism. His symbolic animal is a bull, named Nandi, which is commonly depicted kneeling in front of the Shiva Linga. Pictorial depictions of Shiva always show a crescent-shaped moon in his matted locks, much like the lunar crescent that appears on top of certain baetyls in Petra; and on top of the Shiva Linga is present a coiled-up serpent, bearing a strong resemblance to the serpent monument of Petra.

It is evident that Shiva and Dushara are symbolically identical, leaving little scope for doubt that Dushara must indeed be a representation of the Sanatana Dharma deity Shiva.

Fig 7: Giant Monolithic statue of

Giant Monolithic statue of Nandi, the Bull

Black stone Shiva Linga in the coils of a seven hooded serpent. Lepakshi, Andhra Pradesh

The similarities, however, do not end here. The consort of Dushara was known to the Nabataeans as Al-Uzza or Al-lat. She was a goddess of power and a goddess of the people, and was symbolized by a lion. Lions are present at many sites in Petra. At the Lion Triclinium in Petra there are two massive lions protecting the doorway. Lions are also seen at the Lion Monument in Petra, a public fountain, where refreshing water for the perspiring pilgrims would have sprouted from the water outlet at the mouth of the lion.

At the Temple of the Winged Lions, a considerable amount of material has been found, including feline statuette fragments, which emphasize the ‘feline’ association of the mother goddess. The supreme mother goddess was also symbolically associated with vegetation, grains and prosperity, and was frequently depicted holding cereal stalks and fruits.

Not surprisingly, the lion is also associated with the consort of Shiva, known as Parvati, Durga or Shakti. As per the Puranic legends, when the entire humanity was threatened by the evil Mahisasura, the goddess Durga, invested with the combined spiritual energies of the Hindu Trinity – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva – and adorned with celestial weapons granted by the divine company of gods, rode her lion to battle this asura. The terrible battle raged over nine days, and on the tenth day Durga defeated and killed Mahisasura. Even now, the victory of Durga over the forces of darkness represented by Mahisasura, is one of the most widely celebrated religious festivals in India, known as Dussehra (or Dasha-Hara, Navratri, Vijaydashami) which is celebrated over a period of ten days.

The idol of Al-Uzza, found in the Temple of the Winged Lions

One of the two reliefs of lion of the Lion Triclinium in Petra, Jordan

Durga on a Lion, slaying Mahisarura who has taken the form of a bull. Aihole temple complex, Karnataka

There are indications that the Nabataeans, too, may have celebrated this ancient festival. At Petra, an elaborate processional way leads from the center of the city to the temple of Al Deir. In front of the temple there is a massive, flat, courtyard, carved out of the rock, capable of accommodating thousands of people. This has led historians to suggest that the Al Deir temple may have been the site of large-scale ceremonies.

It is possible that this was a celebration of Dussehra, since Al-Uzza / Al-Lat was the ‘goddess of the people’ and Dussehra is the celebration of the victory of the goddess over the forces of evil. It is not unlikely that the presiding god of the Nabataeans, Dushara, may have obtained his name from the festival Dussehra.

The cult of Shiva-Shakti represented the sacred masculine and feminine principles, and the worship of Shiva has always been inextricably linked with the celebrations of Durga. Even now in rural Bengal in India, the final day of celebration of Dussehra (Basanti Puja) is followed by an exuberant worship of Shiva. For these people, it remains the most important festival of their annual religious calendar.

Interestingly, the Nabataeans worshipped the triad of goddesses – Al-Uzza, Al-lat and Manat – often depicted in Petra in the form of three baetyls, carved next to each other. Al-Uzza (the ‘Strong One’) was the goddess of the morning and evening star. Isaac of Antioch (5th century CE) referred to her as Kaukabta, ‘the Star’. She was the virgin-warrior and the youngest in the goddess triad, fiercely protective, and a strong ally in an approaching battle. She was sometimes depicted riding a ‘dolphin’ and showing the way to sea-farers. She has been identified as the counterpart of the Indo-European goddess of dawn, Ostara, and the Vedic ‘Usas’.

In the Rig Veda, there are around 20 hymns dedicated to the Usas, the goddess of dawn, who appears in the east every morning, resplendent in her golden light, riding a chariot drawn by glorious horses, dispelling the darkness, awakening men to action, and bestowing her bounty and riches on all and sundry. The phonetic and symbolic associations between ‘Uzza’ and ‘Usa’ indicate that they may be derived from the same source.

Al-lat was widely regarded as ‘the Mother of the Gods’, or ‘Greatest of All’. She was the goddess of fertility and prosperity and was known from Arabia to Iran. She was symbolically associated with vegetation, grains and prosperity, and was frequently depicted holding cereal stalks and a small lump of frankincense in her hands. In this respect, Al-lat is symbolically associated with the Hindu goddess ‘Lakshmi’, who is also considered as the goddess of prosperity and fertility, and is depicted holding cereal stalks and a container of grains.

The third goddess of the Nabataean triad, Manat, is the oldest goddess of the Nabataeans, and also the most feared. She was the terrible, black goddess of death, destruction and doom, and was worshipped as a black stone at Quidaid, near Mecca. Nabataean inscriptions tell us that tombs were placed under her protection, asking her to curse violators. The symbolism of Manat bears stark resemblances to the Hindu goddess of death and destruction – Kali – who is also worshipped in the form of a black goddess.

We can, therefore, see that the Nabataean triad of goddesses – Al-Uzza, Al-Lat and Manat – corresponds to the Vedic/Hindu goddess triad– Usa, Lakshmi and Kali. And here is the most interesting part: Even now, this goddess triad is worshipped in many parts of India, with the sole exception that Usa is often replaced by Saraswati, the goddess of learning and wisdom.

One of the most famous temples in India, which attracts millions of devotees throughout the year, is the Vaishno Devi temple in Jammu. This temple is dedicated to the goddess Vaishno Devi, who is an aspect of the goddess Durga. The primary shrine at Vaishno Devi, however, contains three pieces of stones representing the three goddesses – Saraswati, Lakshmi and Kali. It is believed that these three goddesses represent three different aspects of the all-encompassing mother goddess Durga, the consort of Shiva. The symbolic similarities with the Nabataean goddess triad are plainly evident.

Certain rituals associated with Shiva-Durga worship can also be found reflected in the religious practices of the Nabataeans. The Nabataeans ritually made animal sacrifices to Dushara and Al-Uzza, at the ‘High Place of Sacrifice’ in Petra. The Suda Lexicon, which was compiled at the end of the 10th century, refers to older sources which have since been lost. It states:

Theus Ares (Dushrara); this is the god Ares in Arabic Petra. They worship the god Ares and venerate him above all. His statue is an unworked square black stone. It is four foot high and two feet wide. It rests on a golden base. They make sacrifices to him and before him they anoint the blood of the sacrifice that is their anointment.

The practice of anointing the Shiva Linga with red vermilion powder (Kumkum) continues to this date in India. It has also been noticed that most of the Djin blocks (large standing stone blocks) at Petra are located close to sources of running water, a fact which has left historians in a dilemma. However, such a peculiar alignment of Djin blocks can be explained once we remember that one of the most common practices of Shiva worship is to pour a kettle of water (or milk, curd, ghee, honey etc.) over the Shiva-Linga. This act is symbolic of the sacred river Ganges, which, after emanating from the toe of Vishnu, flows down the matted locks of Shiva. This is the reason why nearly every Shiva temple is also associated with a natural well or spring or a source of running water.

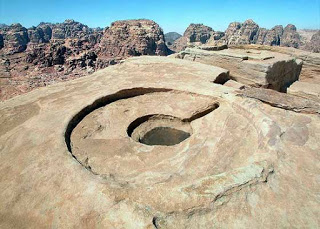

Petra – High Place of Sacrifice. Source: atlastours.net

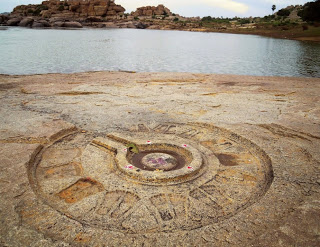

Shiva Linga carved on the bedrock, at Hampi, Karnataka.

The worship of Shiva-Durga, the sacred masculine and feminine principles, is as old as time itself. The presence of sacred pillars and dolmens, the ancient snake cults, the symbolism of the trisula / trident, the crescent moon etc. found at various archaeological sites across the world suggests that the worship of Shiva-Shakti was one of the most deeply entrenched belief systems of the ancient wisdom traditions. Among the ancient Semites, a pillar of stone was a sacred representation of a deity. In many texts, the ancient Hebrews are recorded setting up stones as monuments. Jacob set up a pillar and anointed it, in a manner starkly reminiscent of the Shiva worship rituals, while Joshua set up a sacred stone monument under a oak tree, just as a Shiva Linga is generally set up under a banyan tree:

“And Jacob rose up early in the morning, and took the stone that he had set up for his pillows, and set it up for a pillar, and poured oil upon the top of it. (Genesis 28; 18-19).

“And Jacob set up a pillar in the place where he talked with him, even a pillar of stone: and he poured a drink offering thereon, and he poured oil thereon (Genesis 35; 14).

And Joshua wrote these words in the book of the law of God, and took a great stone, and set it up there under an oak, that was by the sanctuary of the LORD” (Joshua 24;26).

Pillars and Dolmens (stones arranged one on top of another) also constituted an essential part of Druidical worship, among the Celts of ancient Britain and France. In the Irish Druids and Old Irish Religions (1894), James Bonwick mentions that the Irish venerated their lithic temples. They not only anointed them with oil or milk, but, down to a late period, they poured water on their sacred surface so that the draught might cure their diseases. Molly Grime, a rude stone figure, kept in Glentham church, was annually washed with water from Newell well.

Pillars and Dolmens (stones arranged one on top of another) also constituted an essential part of Druidical worship, among the Celts of ancient Britain and France. In the Irish Druids and Old Irish Religions (1894), James Bonwick mentions that the Irish venerated their lithic temples. They not only anointed them with oil or milk, but, down to a late period, they poured water on their sacred surface so that the draught might cure their diseases. Molly Grime, a rude stone figure, kept in Glentham church, was annually washed with water from Newell well.

Fig 13: Cylindrical, Linga-shaped stone in the center of the stone altar. Feaghna, Ireland, at least 2000 years old. Source: http://www.megalithic.co.uk

The geographical distribution of stone monuments extends from the extreme west of Europe to the extreme east of Asia, and from Scandinavia to Central Africa. In spite of centuries of destruction, stone monuments of every type abound in the British and Irish Islands, and some of the most remarkable structures in Europe are found there. In France some 4000 dolmens are present. In Northern and Central Europe they occur in Belgium, Holland and in the northern plains of Germany. They have been found in large numbers in Denmark and the Danish Islands, and also in Sweden. ‘Meteoric stones mounted on carved pedestals’ have been found in the farthest reaches of the Roman Empire, and one such piece is, at present, on view at the Etruscan Museum in Vatican, Rome.

Although this ancient faith was practiced in large parts of the world since time immemorial, there appears to have been a renewed westward thrust soon after the conquests of Alexander, which invigorated the ancient land and maritime trade routes, popularly known as the Silk Route, which connected India and China with the western world.

In 329 BC, Alexander established the city of Alexandria in Egypt, which became a major staging point in the Silk Route. In 323 BC, Alexander’s successors, the Ptolemaic dynasty, took control of Egypt. They actively promoted trade with Mesopotamia, India, and East Africa through their Red Sea ports and over land. This was assisted by a number of intermediaries, especially the Nabataeans and other Arabs. Soon after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, regular communications and trade between India, Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, China, the Middle East, Africa and Europe blossomed on an unprecedented scale.

The Silk Route transformed into a highway for the cultural, commercial, technological, philosophical and religious exchanges between far flung kingdoms. Buddhism spread from the northern part of India into the farthest reaches of China. The Eastern Han emperor Mingdi is supposed to have sent a representative to India to discover more about this strange faith, and further missions returned bearing scriptures, and bringing with them Indian priests.

Together with coveted merchandise, rock-cutting skills travelled eastwards along the Silk Road from India to China. Hundreds of rock-cut caves with statues of Buddha were built between 450 and 525 CE. Among the most famous ones are the Longmen Grottoes in China’s Henan province, a UNESCO World Heritage Site today. The Longmen grotto complex contains 2345 caves and niches, 2800 inscriptions, 43 pagodas and over 100,000 Buddhist images collected over various Chinese dynasties. The Yungang Grottoes near Datong in the province of Shanxi consists of 252 grottoes and more than 51,000 Buddha statues and statuettes, mainly constructed in the period between 460-525 CE.

There was also a westward flow of Eastern wisdom along the Silk Route. During the time around 320 BC, soon after the conquests of Alexander, the Mauryan Empire of India had extended its western borders to include nearly the whole of Afghanistan, and large portions of south-eastern Iran. Chandragupta Maurya had entered into a settlement and matrimonial alliance with the Greeks in 305 BC. Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (modern Patna). The effect that this cultural exchange between two ancient nations had on the flowering of Greek philosophy and sciences during this period has been grossly underestimated by modern historians. In the Preface to the Vishnu Purana (translated 1940), the translator Horace Hayman Wilson, who was the Professor of Sanskrit at the Oxford University, writes:

“We know that there was an active communication between India and the Red sea in the early ages of the Christian era, and that doctrines, as well as articles of merchandise, were brought to Alexandria from the former. Epiphanius and Eusebius accuse Scythianus of having imported from India, in the second century, books on magic, and heretical notions leading to Manichæism; and it was at the same period that Ammonius instituted the sect of the new Platonists at Alexandria. The basis of his heresy was that true philosophy derived its origin from the eastern nations: his doctrine of the identity of God and the universe is that of the Vedas and Puráńas; and the practices he enjoined, as well as their object, were precisely those described in several of the Puráńas under the name of Yoga. His disciples were taught “to extenuate by mortification and contemplation the bodily restraints upon the immortal spirit, so that in this life they might enjoy communion with the Supreme Being, and ascend after death to the universal Parent.” That these are Hindu tenets the following pages will testify; and by the admission of their Alexandrian teacher, they originated in India.”

It is, therefore, quite possible that the ancient faith of Shiva-Shakti may also have migrated westwards along these ancient trade routes during this time, and it was adopted by the Nabataeans. While it is possible that the Nabataeans may have worshipped Dushara prior to the construction of the monuments at Petra, there is very little evidence to support that. And even if they did worship Dushara prior to Petra, the stark similarities between the symbolic elements, rites and rituals of their faith with elements of Shiva-Shakti worship indicates that there must have been a cultural diffusion along the Silk Route which profoundly impacted and reinvigorated their religious beliefs.

The other intriguing question is, how did the Nabataeans suddenly acquire and master the technological and architectural sophistication necessary to execute the rock-cut monuments of Petra? Achieving such a level of finesse and perfection in rock-cut architecture takes generations. In the few centuries before Petra was established the Nabataeans had not constructed a single house in the desert, let alone grand temples. Is it possible that, like the ancient cult of Shiva-Shakti, the technology for building these rock-cut monuments was also transferred along the Silk Route?

It may be no coincidence that around the same time that the rock-cut monuments of Petra were being executed, sometime during the 3rd – 2nd century BC, an incredible array of 31 rock-cut cave temples were being carved into the sheer vertical side of a gorge, near a waterfall-fed pool, located in the hills of the Sahyadri mountains in western India, at a place called Ajanta, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Ajanta is located 100 kilometers from the medieval town of Aurangabad (‘City of Gates’), which is situated right on the ancient Silk Route, and was a flourishing commercial center since time immemorial. In the ancient times, however, Ajanta itself used to be on the Silk Route. Buddhist missionaries used to accompany traders on busy international trade routes through India and the merchants, in turn, funded or even commissioned elaborate cave temple complexes that also offered lodging for traveling traders. Some of the more sumptuous temples included pillars, arches, and elaborate facades. Like Petra, the Ajanta caves had fallen out of use, and remained lost for centuries until 1819, when they were re-discovered by a British officer who was hunting a tiger in the region.

While in Petra only the exterior façade was decorated with sculptures, the cave temples at Ajanta are elaborately decorated, both outside and inside, with sculptures, paintings and murals, which are considered to be masterpieces of Buddhist religious art, and represent the most sophisticated rock-cut architecture of this period anywhere in the world. They mostly depict the Jataka tales that are stories of the Buddha’s life in former existences as Bodhisattva. Many mythic elements from Hinduism are also depicted. Moreover, the interiors were designed to be functional, providing housing, worship halls, and even dining halls for the monks who lived there.

It is extremely improbable that two ancient cities located on the Silk Route, and worshipping deities that are culturally related, would happen to build some of the finest rock-cut temples of the world at around the same time, without having any cultural contact between them. Petra and Ajanta must be connected; and since the rock-cut architecture of India represents the highest achievements of engineering and aesthetics of that period, it can be supposed that the Silk Route acted as a conduit for the westward transfer of the Shiva-Shakti cult and rock-cut architectural skills, across the Arabian Peninsula, during the 3rd – 2nd centuries BC. However, since Petra stood at the crossroads of the trade route between the east and the west, there has been an amalgamation of various influences in its architecture. The Greco-Roman influence is apparent in the facades of many structures, which strengthened even further after the Roman occupation of Petra. Egyptian influences are also evident due to the presence of obelisks and funerary tombs throughout the city.

Many other rock-cut architectural sites were established along the Silk Route during this period. For instance, the monolithic Buddha statues and rock-cut monasteries of Bamiyan in Afghanistan were constructed between the 2nd – 7th centuries CE, while at Taq-e-Bostan in the Kermanshah Province of Iran a set of beautiful rock-cut caves and reliefs were built between the 3rd – 7th centuries CE. Both places are located right next to the ancient Silk Route.

The Nabateans built a few other cities in the desert, one of which is the archaeological site of ‘Shivta’ built in the 1st century BC on the ‘Perfume Road’ between Petra to Gaza. Like Petra, Shivta too was abandoned by the 8th – 9th century CE, after the ascendancy of Islam.

A few kilometers from Shivta is located the ancient, biblical city of ‘Tel Sheva’, an archaeological site in southern Israel, which derives its name from a nearby ‘well’ or ‘water source’. The phonetic and symbolic similarities between these cities and ‘Shiva’ are obvious. In fact, the worship of Shiva-Shakti was widespread across the entire Middle East and West Asia, and penetrated deep into the farthest corners of Europe in the centuries before Christ. The biblical kingdom of ‘Sheba’ (Hebrew: Sh’va) believed to be in present day Yemen, as well as the archaeological site of ‘Shibham’ (Sanskrit: Shivam) located in Yemen, hint at the fact that entire kingdoms and cities were named after this deity.

It is unfortunate that these symbolisms and associations have been either overlooked or ignored by historians till now. What is even more regrettable is the fact that the Shiva Linga, and, in fact, any Pillar or Dolmen cult, has been uniformly interpreted as a form of phallic worship, when the information from the ancient sources clearly specify that the ‘pillar’ represents the ‘Cosmic Mountain’, the symbolic axis-mundi of the cosmos, around which the heavens revolve.

It is a powerful cosmic symbol, fusing the divine masculine and feminine principles, whose meaning was universally understood by the ancient cultures, but whose real import has been lost to us now. Unless we begin to acknowledge the widespread presence of the Shiva-Shakti cult in large parts of the ancient world, and make a sincere attempt to understand the vast array of symbolisms associated with this ancient faith, we will continue to concoct a version of history that is illusory, fragmentary, and ultimately meaningless.

Author:Bibhu Dev Misra

Image Courtesy: National Geographic

You may also like

-

Global Dance Overture Brings Indo–Russian Cultural Harmony to Kamani Theatre

-

Kharavela: The Lion of Kalinga Who Rewrote Power, Piety and Prestige in Ancient India

-

INSV Kaundinya Returns to Mumbai: A Voyage that Revives India’s Ancient Maritime Glory

-

The Forgotten War on the Western Coast: The Story of Rani Abbakka Chowta

-

Cabinet Approves Alteration of the Name of the State of “Kerala” to “Keralam”