Pagodas are a dominant and attractive feature of the cultural landscape of China. These towering, multi-tiered structures generally have an odd number of tiers (between 3 and 15) signifying the many levels of heaven inhabited by the Buddhas.

The construction of pagodas began in China in the 1st century AD with the advent of Buddhism. The arrival of Buddhism took place under interesting circumstances.

According to legends, Emperor Ming (58-75 AD) of the Eastern Han Dynasty once dreamt of a golden man, more than three meters tall, with a halo above his head, who came near his throne from the heavens and circled his palace. When he asked his ministers to interpret the dream, one of them, Fu Yi, told him that in the West (India) there is a god called Buddha, and the golden man that the emperor saw in his dream resembled him. The emperor then dispatched his emissaries to find out more about this new faith. In Afghanistan, they met two Buddhist masters from India – Kasyapa Matanga and Dharmaratna – and persuaded them to return to China. The two monks agreed, and brought Buddhist scriptures, relics and statues of Buddha with them, on two white horses.

On their arrival at Luoyang, the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty, Emperor Ming gave them a warm welcome, and built the White Horse Temple (68 AD) – the first Buddhist temple of China – for them to live in, naming the temple in honor of the two white horses that carried them there. Here, the monks resided till the end of their lives, translating Sanskrit texts into Chinese. The White Horse Temple increased in importance as Buddhism prospered from here. Many regard this temple as the “cradle of Chinese Buddhism”. The original temple was destroyed in a fire in the 12th century AD, and was reconstructed subsequently.

Historians have suggested that the development of the pagoda in ancient China was influenced by the Buddhist stupa architecture fused with the Han dynasty tradition of erecting multi-storied watchtowers. During the Han dynasty (c.206 BC – 220 AD), prior to the advent of Buddhism, the Chinese used to build multistoried buildings with upper, inhabitable floors, and many levels of projecting roofs. They functioned both as houses as well as watchtowers. The watchtower was usually placed at the back of the compound for defensive purposes. Some of the towers had a drum hung in it as a warning device (drum-towers).

While the similarities between the Han dynasty watchtowers and the pagodas are easily evident, there is practically no resemblance between the Buddhist stupa and the Chinese pagoda.

The hemispherical stupa dome – the most prominent part of the stupa – is completely absent in a Chinese pagoda. The stupa dome houses the cremated remains (sarira) of the Buddha or a Buddhist saint, but a Chinese pagoda may or may not contain relics (although they invariably contain a statue of the Budhha in the lower storey, indicating its importance as a place of worship). The prominent flight of stairs that leads to a stupa dome is also absent in a pagoda. The suggestion that the stupa spire, consisting of a stack of circular discs or parasols, evolved into the multi-tiered pagoda, is not convincing either. Each level of the pagoda has windows and balconies (like the Han dynasty watchtowers). Sometimes an inner spiral staircase connects the different tiers. This is of an entirely different level of complexity than the simplistic stupa spire.

It seems very unlikely that the Buddhist stupa had any influence on the Chinese pagoda design. In fact, stupas were not popular in China at all, and very few stupas can be found in China today. In some other countries of South-East Asia, such as Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia, however, stupas evolved into temples called pagodas. Here the essential stupa characteristics – the hemispherical dome, ascending stairs, and spire – can be easily identified.

So, the question is what led to the development of the Chinese pagoda, soon after the advent of Buddhism?

My hypothesis is that the Han dynasty tradition of building multi-storied towers was fused with Hindu temple architecture to create the pagoda designs. Both Buddhism and Jainism, the two new faiths that emerged in India in the 6th century BC, had adopted the principles of Hindu temple architecture. This temple building tradition passed on to the Chinese, aided by the visits of a large number of Chinese pilgrims who came to India between the 5th – 9th centuries AD, and carried back with them voluminous Sanskrit texts.

Let us look at a few specific examples to identify the correlations.

North Indian Temple Shikhara

The oldest surviving Chinese pagoda – the 12 sided brick pagoda of the Songyue temple complex built in 523 AD – has a predominantly Indian design. This has not escaped the notice of historians. The Encyclopedia Britannica states: “the brick and stone pagodas, which were originally more Indian in form and were gradually Sinicized…The oldest surviving example is the Songyue Temple, a 12-sided stone pagoda on Mount Song (c. 520–525) that is Indian in its shape and detail.”

The 15-tiers of the Songyue pagoda gradually recede towards the top, such that the overall profile resembles the curvilinear tower (shikhara) of a typical North Indian Hindu temple. The temple has 12 sides, although most pagodas have a circular, square, hexagonal or octagonal base – which is consistent with the diversity in the layout of Hindu temples. It is crowned with a finial which resembles the “pot containing the nectar of immortality” (amrta-kalasa) on top of a Hindu temple. The pagoda has four entrances aligned to the cardinal directions, while the remaining eight sides have arched niches decorated with lion motifs. The pillars have lotus-bud capitals. Overall, the influence of Hindu temple building styles is conspicuous.

Many other brick pagodas such as the Small Wild Goose Pagoda (709 AD) or the Liaodi Pagoda (11th century AD) – the tallest brick pagoda in the world at 84m – also have gradually-tiered eaves, resembling the North Indian shikharas. Of course, the designs have been adapted to blend in with the traditional Chinese architecture, but the similarities are quite prominent, as can be seen by comparing with some of the North Indian style Hindu temples.

The visual resemblances are so striking that the Portuguese used to refer to Hindu temples as pagodas. The towering spire of the Sun Temple at Konark, Orissa (built in the North Indian style) was known as the “Black Pagoda” to the European sailors.

The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya, India, also exerted a significant influence on pagoda styles. This temple was built at the place where Sakyamuni Buddha had attained enlightenment sitting under a Bodhi tree.

The Mahabodhi Temple

The Mahabodhi Temple was built in the 5th century AD in the panchayatana style (pancha=five, yatana=gods) of Hindu architecture, where-in the central towering shrine is surrounded by four smaller shrines. This follows from Hindu cosmological ideas: the towering central spire represents the Mount Meru, the cosmic axis-mundi, while the four subsidiary temple spires represent the four mountains which buttress Meru on the four sides.

Interestingly, the straight-edged pyramidal tower of the Mahabodhi Temple is built in the pattern of the Dravidian vimanas. This indicates that the Buddhist temples were amalgamating different architectural styles. Unfortunately, no other Buddhist pagoda-temple prior to the 10th century AD survives in India, although their widespread existence was noted by Fa-Hien and other Chinese pilgrims.

The Mahabodhi Temple was very popular amongst the neighbouring Buddhist countries of India. Adaptations of the Mahabodhi Temple were built in Thailand, Myanmar and Nepal. The design passed on to China at an early date for a mural in the Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang (c. 557-581 AD) depicts the panchayatana model. Five pagodas stand on a square platform; the one in the middle is much bigger and more spectacular than the ones at the four corners. Each of the five pagodas has seven storeys with a precious bead on top.

The Zhenjue Temple (or Five Pagoda Temple) of Beijing was built in the panchayatana style in 1474 AD, in imitation of the Mahabodhi Temple. The inscription on the tablet erected upon completion of the pagodas in 1474 says, “the five statues of Buddha are enshrined in five pagodas whose size and design are the same as those of pagodas in India. In reality, however, the sizes and relative proportions of the five towers of the Zhenjue Temple differ significantly from that of the Mahabodhi Temple.

Some Chinese pagodas also contain distinct Dravidian influences. It is possible that these stylistic elements were picked up as Buddhism spread to southern India, and Dravidian building styles were added into Buddhist temples.

The Dravidian Gopurams

Initially, Chinese pagodas were built in the center of the temple compound, along the straight axis from the temple gates. They had a square base, and were seven or nine storeys high. Behind the pagoda was the main hall (vihara) for prayers and rituals, with additional verandas and halls on either side. This is similar to the North Indian temple complex, where the temple is the central and highest structure, surrounded by many pillared halls (mandapas) for carrying out rituals and ceremonies.

Sometime during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 AD), however, the pagoda was moved beside the hall, or out of the temple compound altogether. The main hall replaced the pagoda as the center of the temple.

When the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang returned to China after his 17 year overland journey to India, he built his own monastery at Xi’an, the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda (652 AD) in this style during the Tang dynasty. It stored sutras and figurines of the Buddha that he had brought from India.

This pagoda was in the news recently when the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was received by the Chinese President Xi Jinping in his hometown Xian, and taken for a tour of the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda.

This reflects the design of the Dravidian temple complexes where the entrance tower (gopuram) is the tallest and most imposing structure, while the primary shrine is a small pillared hall. Many pagodas with square bases look very similar to the gopurams. Like the pagodas, gopurams have gradually receding tiers, with doors / windows at each level, and a flight of stairs that takes one to the top floor.

Another set of very important religious / ceremonial structures of Hindu temple architecture (that are often ignored) are the various types of stambhs i.e. pillars erected as memorials. Some Chinese pagodas bear an uncanny resemblance to the stambhs as well.

The Stambhs (Memorial Pillars)

Stambhs were erected for different purposes:

- Vijay stambh i.e. “Tower of Victory” was erected to commemorate a king’s victory in a specific campaign.

- Kirti stambh i.e. “Tower of Fame” was erected in honor of a person who had acquired fame and recognition.

- Dhwaja stambh is flag post of the deity in a temple, on which a flag was hoisted on special occasions.

- Deepa stambh i.e. “Tower of Light” was erected within the temple compound for lighting oil lamps. When the entire pillar was lit up, by placing oil lamps in the niches / arms of the pillar, it transformed into a pillar of light, symbolizing Mount Meru.

Buddhists in India had adopted the practice of constructing multi-storied buildings, in the manner of stambhs. The library at the Nalanda University had a nine-storeyed building called Ratnodadhi which housed the most sacred manuscripts.Jains had also adopted the practice of erecting stambhs, for the Kirti Stambh within the Chittorgarh Fort Complex, Rajasthan, erected in the 12th century by a Jain merchant, was dedicated to the first Jain Tirthankar, Sri Adinath.

A simple visual comparison indicates that pagoda designs may have been influenced by the architecture of stambhs.

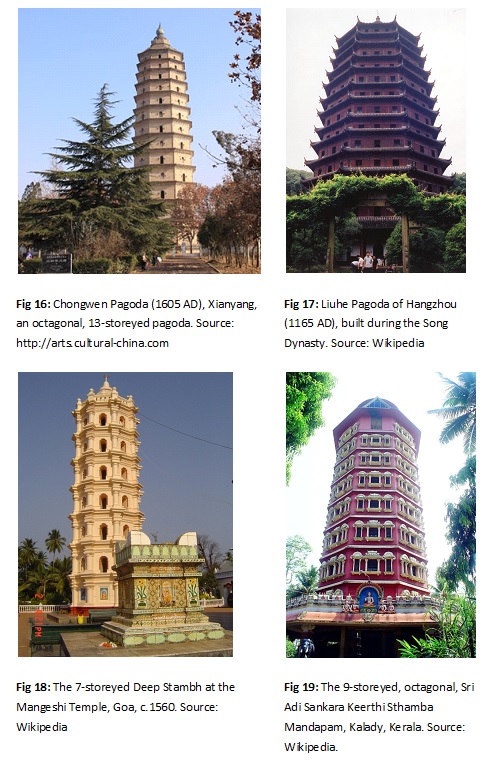

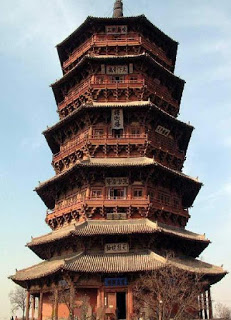

Finally, let us look at the wooden pagodas, which were the earliest pagodas built in China.

Wooden Temple Pagodas

The first pagodas built in China were wooden structures, none of which have survived till the present day.

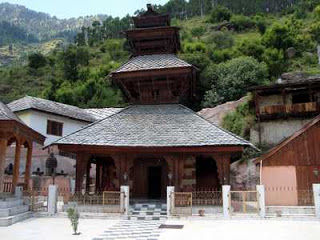

The oldest wooden pagoda standing in China today is the Sakyamuni Pagoda of Fogong Temple built in the 11th century. In India too, wooden temple pagodas dedicated to Hindu gods were popular in the western Himalayas, particularly in the state of Himachal Pradesh. The multi-storeyed wooden pagodas of Himachal Pradesh mostly date from around the 14th century, but there has been a very long tradition of building similar structures. They resemble the Tibetan Buddhist temples, and some of the wooden pagodas of China and Japan.

Did the tradition of constructing wooden temple pagodas get transferred from India to China, or was this tradition widely prevalent in the Himalayan region prior to the advent of Buddhism? Since the Han-era watchtowers of China look similar to the wooden pagodas, the second possibility seems more likely i.e. this style of temple building was indigenous to the Himalayan region before the advent of Buddhism. However, the designs were influenced by Buddhism subsequently.

Interestingly, the tiered pagodas of Japan are called Shumisen meaning “Sumeru” – a term which refers to the central axis of the universe, Mount Meru, in the Hindu-Buddhist tradition.

Conclusion

This brief comparison of Chinese pagodas and Hindu temples is an attempt to show that, contrary to the oft-repeated premise, Chinese pagodas were not influenced by the stupa architecture. Instead, there is a strong possibility that Chinese pagodas developed from a fusion of the Han dynasty tradition of building multistoried watchtowers, with many elements of Hindu temple architecture such as the North Indian style curvilinear shikharas, the panchayatana style of the Mahabodhi Temple, the Dravidian style gopurams, and the many different types of stambhs such as the Vijay stambh, Kirti stambh, Dhwaja stambh and Deepa stambh.

These stylistic elements were incorporated into the Buddhist (and Jain) temples of India, and were transmitted to China by a long stream of Chinese pilgrims (around 188 in number), who visited India between the 5th – 9th centuries AD. The cultural exchanges were further facilitated by diplomatic relations between the Tang emperors of China and the court of King Harshavardhana at Kanauj, since the time of Hiuen Tsang’s visit to India. The connections deserve to be explored further by Sino-Indian scholars.

Author: Bibhu Dev Misra

Image Courtesy: China Discovery

You may also like

-

Global Dance Overture Brings Indo–Russian Cultural Harmony to Kamani Theatre

-

Kharavela: The Lion of Kalinga Who Rewrote Power, Piety and Prestige in Ancient India

-

INSV Kaundinya Returns to Mumbai: A Voyage that Revives India’s Ancient Maritime Glory

-

The Forgotten War on the Western Coast: The Story of Rani Abbakka Chowta

-

Cabinet Approves Alteration of the Name of the State of “Kerala” to “Keralam”