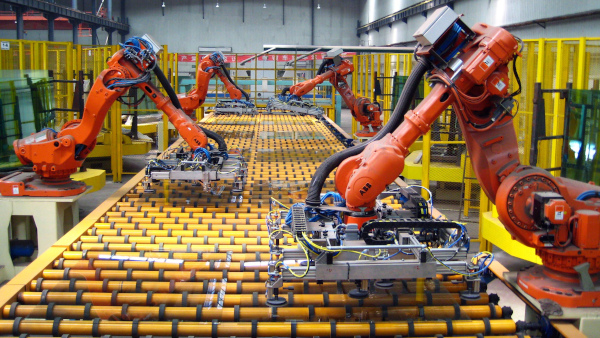

When the robots hum in unison, one split air conditioner (AC) can be made in 23 seconds flat. Humans play second fiddle at home appliances maker Lloyd’s highly-automated factory in Rajasthan’s Ghiloth. About 100 men and women in blue tees and caps assemble the manufactured components and screw-in the compressor and the electronic controllers, before the finished ACs are shifted to testing labs.

A “self check” poster at the start of the assembly lines urges the workers, particularly men, to keep well-groomed hair, be clean shaven. The workers cannot sport a watch or wear rings. The poster hasn’t yet been updated to urge the workers to regularly wash their hands with soap and water.

But then, this plant, which started production in September 2019, appears to be an outlier—the coronavirus epidemic hasn’t disrupted operations much even as global supply-chains are facing a meltdown due to factory shut downs in China since February of 2020.

Some Indian factories are running at half their capacities since manufacturers, overall, are heavily reliant on China for components. India’s overall imports from the Middle Kingdom totalled $70 billion in 2018-19 and the trade deficit runs at over $50 billion.

Lloyd wasn’t an outlier three years ago. The company sourced nearly everything from China. Havells India Ltd acquired the consumer business of Lloyd in 2017 and planned local manufacturing. From little local components in its bill of materials around 2017, the products made at the Ghiloth plant now have 60% domestic components. Just the compressor and the controllers— the remaining 40% per cent—are imported from China. In another six months, the company hopes to start domestic production of controllers. That would further shoot up the Indian value addition.

“By July of 2020, the local value addition would go up to about 75-80%. The compressor would be the only imported product,” said Shashi Arora , CEO of Lloyd. “Similarly, our washing machines were entirely China-sourced till about a year ago. Now, we moved part of the production within India,” he added.

Slowly but surely, other manufacturers are slashing their dependence on China, too. Apart from home appliance companies, the list includes mobile phone makers and lighting companies. An analysis by consulting firm Frost and Sullivan puts the home appliances market at ₹85,300 crore in 2019-20. Less than half this demand is currently met by domestic manufacturing.

Access to Indian consumers

One way to understand the de-risking journey thus far is to look at the capacity expansion of Indian companies who are contracted by many home appliance and mobile handset brands to locally manufacture their products. Five years ago, Dixon Technologies (India) Ltd, an electronic manufacturing contract manufacturer, assembled five million phones a year. Today, it makes 24 million for many multinationals.

“Dixon made 50 million bulbs five years ago. Today, we do 250 million. Similarly, our washing machine production has increased from 300,000 to a million units a year in the same period,” said Sunil Vachani, chairman and managing director (CMD) of the company.

The de-risking trend is all set to accelerate further because of the coronavirus pandemic. The scare, however, wasn’t around five years back. What forced companies to reduce their imports from China? There are a bunch of reasons but the most prominent is the government of India’s import substitution strategy that started levying high customs duties on the import of finished products and components.

The question is why was import substitution necessary? Does it help domestic consumers? Can it create enough jobs considering that manufacturing is getting highly automated? Import substitution, often, doesn’t build export competitiveness—so what happens if aggregate demand in the Indian economy falls?

There are no easy answers but Sunil Kumar Sinha, principal economist and director public finance at India Ratings and Research Pvt Ltd said that the import substitution strategy has to be seen from the context of global protectionism. “The tariffs are in response to changes in the global landscape where India is at a disadvantage because of tariff and non-tariff barriers being erected by other countries. Second, the focus is on Make in India,” he said. The Make in India initiative was launched in September of 2014 with an aim to make India a global design and manufacturing hub.

Some amount of protection is required against the dumping practices of China as well, but for how long is the question, according to Sinha. “Unfortunately, in India, once you provide a subsidy or any kind of protection, it becomes a rule rather than an exception. We don’t know how to roll it back,” he said. Customs barriers, he added, wouldn’t harm a consumer in segments where there are enough domestic and international manufacturers—the standard of the product would be high as well as cost competitive.

De-coupling handsets

The mobile handsets industry is a case in point. Around 120 mobile handset manufacturing units mushroomed in India since 2014, according to India Cellular and Electronics Association, a trade body. After Nokia’s Sriperumbudur plant near Chennai shut down because of two tax disputes, the centre of gravity for phone making gradually shifted to Noida. But the import substitution strategy encouraged assembly of the phone. The components weren’t manufactured. Besides China, a smartphone often has components from countries such as Korea and Taiwan.

Sanjeev Agarwal, the chief manufacturing officer of Lava International Ltd, refused to shake hands when this writer met him at the company’s factory in Noida. He offered a namaste, instead.

The coronavirus pain runs deep at the company. The cost of Lava’s logistics have shot up dramatically ever since the crisis hit, post the Chinese New Year holidays in February. Agarwal, nevertheless, appears happy at the progress of the company’s localization strategy.

Before 2015, Lava imported all its phones from China. The company noticed quality issues with many of its imports. The labour costs were rising too. In India, the entry level salaries start between ₹12,000 and ₹15,000; salaries in China are three times higher. Then came the government nudge to localize. “We decided to localize a few parts each year, starting with chargers, battery, ear phones—those were easier to begin with. The duty barriers helped us in mitigating the costs,” Agarwal said.

Now, almost 35% of the company’s feature phones by value is localized. Noticeably, Agarwal’s visiting card has “#ProudlyIndian” printed on it.

The government first announced a countervailing duty on mobile phone imports in the Union budget of 2015-16. Since then, there have been steady increases in customs duties on various mobile handset parts. The printed circuit board assembly (PCBA), which is considered the smartphone’s brain, was also included.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s budget of February 2020-21 has further tightened the screws on mobile-related imports. From October 2020, the duty on display panel and touch assembly will rise to 10% from nil. Display and touch panel manufacturing is capital intensive and constitutes about 25% of the cost of making a mobile handset. These panels are imported from China right now.

“For the future, Lava will work on display and camera modules. We are working with our suppliers who are putting up plants. There are Chinese companies, some are joint ventures. The localization content in smartphones would go up soon,” Agarwal said.

The Indian bulb

Meanwhile, the localization content in LED bulbs is getting brighter. The broad script is similar to mobile phones. While manufacturers assemble in India and have reduced dependence on China for low-value work, component manufacturing is yet to take root.

“We are far more detached from China than what we were a few years back,” said Sumit Joshi, the chief executive of Signify Innovations India Ltd, the new avatar of Philips Lighting India Ltd. “About 98% of what we sell in India is made in India. I don’t depend on China for finished goods,” he added.

Joshi said the dependence on Chinese components is dwindling. “We are now able to make 60% of the components in India,” he said. Lighting components imported from China include LED chips, transistors, and resistors.

There are two reasons why lighting companies de-risked from China. Indian consumers behave differently from global consumers and two, the Indian government became a big buyer.

The Union government’s Unnat Jyoti by Affordable LEDs for All (UJALA), a scheme to provide LED bulbs to consumers and replace 770 million incandescent bulbs, began in 2015. The overall LEDs distributed through the programme totals over 360 million until 16 March 2020. Since the mandate was to make bulbs affordable, LED makers started developing local supply-chains.

How are Indian consumers different? Joshi cites the example of the still-preferred tube light in Indian homes. “We came up with the Philips T bulb. It is more of a horizontal kind of a bulb because Indian consumers like brightness and a throw of light,” he said.

To switch over from conventional lighting to LEDs, Indian consumers also demanded longer warranties. Signify offers a two-year warranty on a bulb, a small value product. It can’t afford returns. The company, therefore, ensures that the bulbs tolerate power surges, common in many parts of the country. This customization ensures that lighting companies are less dependant on imports.

The quality imperative

Back to Lloyd’s Ghiloth factory where the machines dominate men. Most greenfield factories set up since 2015 are highly automated. Automation implies standardization and thereby, a higher standard of the final produce. Arora quipped that the product quality in the Ghiloth plant is best in class since human intervention is less.

Like Signify, the company can now offer long-term warranties. “We offer a 10-year warranty on AC compressors as well as on washing machine motors. To be able to offer this, you need to have a positive control on production. We know what goes in the machine because everything is done from scratch. The bill of materials is controlled,” Arora said.

The quality imperative to de-risking from China is palpable at Godrej Appliances, as well. Around 2014, the company imported many finished products from China—ACs, washing machines, deep freezers. “Today, we manufacture the entire washing machine range in-house. We have set up new lines, expanded capacity in ACs. All this has been done over the last four-five years,” Kamal Nandi, business head and executive vice-president of Godrej Appliances said.

The firm’s manufacturing capacity for inverter split ACs is expected to grow from two lakh to four lakh units in three years.

The import duty structures certainly played a role in pressing the localization button. In September 2018, the central government announced higher tariffs to curb import of many home appliances with an aim to “narrowing the current account deficit”. The basic customs duty on ACs, refrigerators and washing machines less than 10kg spiked from 10% to 20%. Nandi, nevertheless, stressed that Godrej Appliances also wanted to be more competitive.

“One of our focus is lean and green operations. It is possible when you localize,” Nandi said. “This was paramount because we were competing against the best of brands in the world. Unless we were competitive enough, we wouldn’t have been able to scale-up. If you have to be lean, you have to be lean across the supply-chain,” he added.

While lean supply-chains are about delivering products quickly to the consumer, reducing costs as well as wastage, being green is about cutting down on the carbon footprint. Most companies, perhaps, are now realizing that a local supply-chain, besides being greener, can cushion against black swan events such as the coronavirus pandemic.

Source: LiveMint

Image Courtesy: Amrita

You may also like

-

India’s Strategic Rise Through Free Trade Agreements: Achievements and Impact (2025–26)

-

Reforming for Growth: How Policy Changes Are Transforming India’s Business Environment

-

India to Build First Riverine Lighthouses on Brahmaputra to Boost Inland Waterway Navigation

-

India Assures Energy Security Amid Rising Tensions in the Middle East

-

GPS Technology Transforms Fishing Livelihoods in Car Nicobar