Sometime this week, MV Maheshwari carrying 53 containers will leave the Haldia port near Kolkata for Pandu port in Guwahati, carrying freight for Hindustan Petrochemicals and Adani Wilmar. Shipping secretary Gopal Krishna will likely flag off the vessel. Over 12-15 days, it will cover 1,489 kilometres, passing through Bangladesh, along the well-worn Indo-Bangladesh river trading route at first, and then traversing a little-used course that could dramatically alter the connectivity to the northeast of India.

India’s northeast is a prisoner of geography. Landlocked and ring-fenced by neighbours such as China, Bhutan, Myanmar and Bangladesh, its lone land-based connection with the rest of India is narrow—the 22-km wide ‘chicken’s neck’ in Siliguri—and strategically speaking, easy to disrupt. This means the land-based networks of transport and trade, the lifelines through which goods, progress and prosperity flow, are limited, far-flung and congested.

India has always thought of this problem as having a two-pronged solution. One, activate the river networks in this area to boost maritime trade. Secondly, one of the southern points of the northeast, Agartala, is tantalisingly close to the ocean—just 200 km away, separated by foreign territory. Land-based access to ports there will hugely boost connectivity. But the execution of both parts hinges on Bangladesh and have been tied up in bureaucratic wrangling.

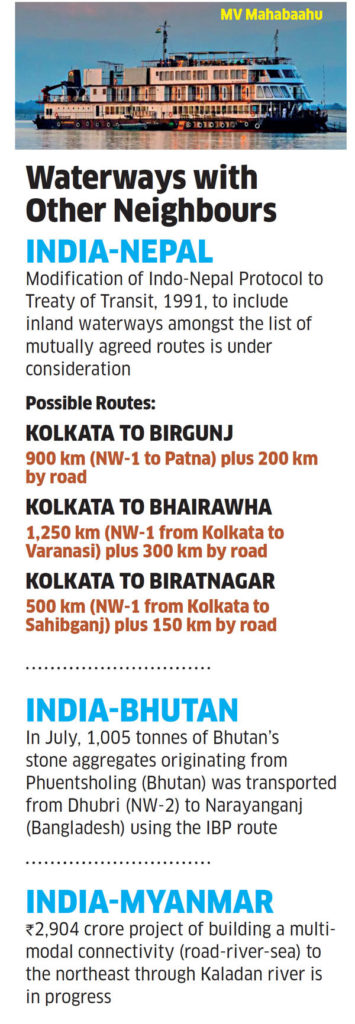

Earlier this month, when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina visited New Delhi, important levers in this regard were pushed into action. The Gangetic network used for the growing Indo-Bangladesh trade, which currently extends from Kolkata to the Narayanganj port near Dhaka, can be extended to reach different points in the northeast—Silghat in middle Assam through the Brahmaputra river (called Jamuna in Bangladesh) and Karimganj in the south of the state through the Kushiyari river. These routes are part of the Indo-Bangladesh Protocol for Inland Transit and Trade (IBPITT) but had fallen into disuse due to various challenges over the years. Efforts are now on to breathe new life into them.

Connecting Agartala by road to ocean ports in Chittagong and Mongla in Bangladesh, just 200 km away, is the other initiative that is now gathering pace. All of this is happening against the backdrop of growing trade between India and Bangladesh, where frenetic construction activity is creating an insatiable appetite for fly ash—the key ingredient in the manufacturing of cement—from India.

Trade Ties

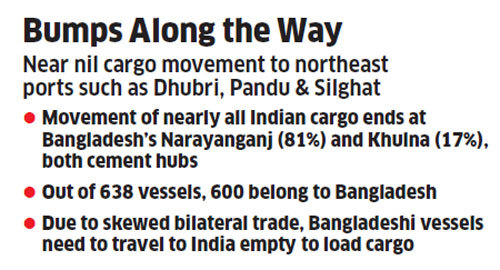

Bilateral trade between India and Bangladesh was worth $10.25 billion (Rs 71,730 crore) in FY2018-19. India enjoys a trade surplus of $8.16 billion. Bangladesh mainly imports fly ash from India via the river route. Currently, 98% of the cargo that travels from India to Bangladesh via rivers ends at Narayanganj and Khulna, both vibrant river ports located in districts with jute and cement factories.

Located on the banks of Shitalakshya river, a distributary of the Brahmaputra, Narayanganj is just 30 km south of Dhaka. And by the river route, it is 910 km away from Kolkata.

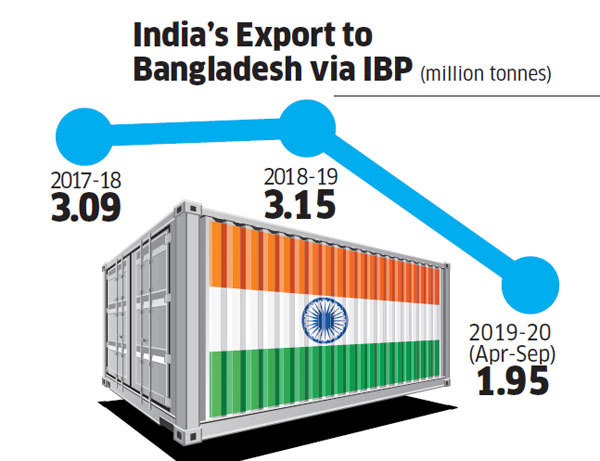

Khulna, on the other hand, is sandwiched between the banks of two rivers — Rupsha and Bhairab, both distributaries of Ganga. And it is closer from Kolkata — just 523 km by river. These two hubs play a key role in making Indo-Bangladesh trade ties vibrant — in 2018-19, 3.15 million tonnes of cargo moved through this route, up from 3.09 million the previous fiscal.

Figures with the Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) show trade this fiscal is on track to cross 4 million tonnes and close to 4,000 voyages. World Bank has recently estimated Bangladesh’s growth projection for FY 2019-20 to be 7.2%, as against India’s 6%.

The dominance of just one commodity on the riparian trade routes, and their termination in Narayanganj makes one thing clear — New Delhi hasn’t succeeded in expanding the Indo-Bangladesh Protocol (IBP) routes, devised way back in 1972, as a viable transit for the landlocked Northeast. Renewed efforts in this direction, however, are now underway.

The major obstacle holding trade back on two critical routes towards the northeast via Bangladesh are two lowdepth stretches that need dredging. Work is currently underway between Sirajgang and Daikhowa (175 km) on Jamuna (Brahmaputra) river and Ashuganj and Zakiganj (295 km) of Kushiyara river and it is scheduled to be completed in 2021.

For all-season navigation, a depth of 2.5-3 metres is essential. With dredgers, a 45–50 metre wide channel within the river is dug to achieve that depth. At present, 12 dredgers are pressed into action in the IBP routes, according to IWAI records. The work is going to cost Rs 306 crore. India is bearing 80% of the cost. The work includes the cost of maintenance for five years. The IBP connects National Waterway-1 (Ganga, Bhagirathi, Hooghly) with NW-2 (Brahmaputra) and NW-16 (Barak) via Bangladesh channels including Padma, Jamuna, Kushiyara, Meghna et al.

The agreed routes under the protocol include a 1,720 km-long Kolkata to Silghat (middle Assam) stretch and another 1,318 km-long Kolkata-Karimganj (south Assam) segment. The IBP pact is valid till next year, with an embedded auto-renewal provision for five more years. But the fact that four out of six functional river ports on the IBP route—Dhubri, Pandu, Silghat and Karimganj — all located in Assam — are not doing enough freight business, clearly indicates that the IBP has failed to leverage its true potential.

This is why the movement of the container vessel this week from Haldia to Pandu is significant. Along with it, two other vessels — MV Aai and MV Beki — carrying coal will proceed from Haldia before crossing the river channels in Bangladesh to enter into the Brahmaputra. A vessel that has a cargo carrying capacity of 80 to 100 trucks usually move at a speed of 12-15 km per hour.

Dhubri port, located in western Assam, did some business in July this year, when 1,005 tonnes of stone aggregates originating from Bhutan’s border town of Phuentsholing were transported from Dhubri to Narayanganj using the IBP route, a first-of-its-kind initiative involving a third country.

A river journey from Kolkata to Tripura’s capital, Agartala, is shorter by 500 km, compared with road or rail journeys through Siliguri corridor of north Bengal. Apart from the lower cost, it will also decongest and derisk the Siliguri corridor from a strategic point of view. It is deemed vulnerable because of its proximity to China.

India has always aspired for creating an alternative route via Bangladesh in case of exigencies for movement of troops and tanks. “I am quite optimistic of the prospects of transit via IBP route,” says Amita Prasad, chairperson of IWAI. Based on studies conducted by EY for IWAI, the agency is hoping that gradually parts of the 50 million tonnes of annual cargo movement between northeast and mainland India can be shifted to river channels.

Presently, the movements take place only via the chicken’s neck. The goods that NE supplies to the rest of India include cement and clinker, fertilisers, horticulture products, crude oil and tea, just to name a few, whereas the items such as food grains, cement, iron and steel, medicine, automobile, consumer durables and fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) are being brought in from the rest of India.

Ocean Route

A year ago, Bangladesh gave its nod to India to use Chattogram (Chittagong) and Mongla sea ports for transit cargo. The agreement was formalised in October. This may give a huge fillip to a cost-effective transportation to the northeast, helping states such as Tripura and Mizoram, which are geographically more disadvantaged. While the road distance from Kolkata to Agartala is 1,500 km, Chattogram to Agartala via Akhaura is a mere 250 km.

Talking to ET Magazine over the phone, Assam Chief Minister Sarbananda Sonowal said that India’s access to the Bangladesh ports would be hugely beneficial for the entire northeastern region. “During the British era and even after Independence, till 1965, Assam had direct access to the sea ports through today’s Bangladesh. Thanks to Prime Minster Modi’s initiatives, the old routes are getting revived. The transportation cost for carrying goods to the Northeast will reduce substantially. Also, we will be able to export our products through Bangladesh ports.”

But the question is, how will New Delhi incentivise Dhaka to agree to its proposal of perennial transit movement of Indian vessels, especially considering the trade balance that is unfavourable to Bangladesh?

India may have diplomatic muscle, but this question may dwarf the other issues such as the need for dredging and ensuring safety during transit. Though Bangladesh possesses 600 registered vessels (as against India’s 38) on the route, most of those need to sail empty to the Indian ports for loading its goods. The trade is clearly mostly a one-way traffic.

“Bangladesh is allowing its Chattogram and Mongla sea ports for India’s transit goods because it’s a win-win situation for it. The move will increase their business and provide employment to their people. For us, it will be a shorter and cheaper route,” says Anil Bamba, former chairman of Land Ports Authority of India, a government agency dealing with border trade facilities.

As the issues relating to cargo movement via Bangladesh continue to be a talking point, three luxury passenger vessels, including one Bangladeshi flag-bearer, successfully undertook four cross-border voyages since March this year, carrying about 300 tourists, mostly foreign nationals. Two of those voyages were undertaken between Kolkata and Guwahati, thus crossing the entire river system of Bangladesh, including the stretches where the dredging is on.

This tourism initiative has helped address one more issue — safety and security. When foreign tourists sailing days and nights through the Bangladeshi countryside feel safe and comfortable, why fear carrying goods in a cargo vessel? It might be premature to hold out too much hope but the bountiful rivers of Bangladesh holds vast potential help usher development and prosperity into the landlocked northeastern states of India.

Source: ET

Image Courtesy:SASEC

You may also like

-

India’s Strategic Rise Through Free Trade Agreements: Achievements and Impact (2025–26)

-

Reforming for Growth: How Policy Changes Are Transforming India’s Business Environment

-

India to Build First Riverine Lighthouses on Brahmaputra to Boost Inland Waterway Navigation

-

India Assures Energy Security Amid Rising Tensions in the Middle East

-

GPS Technology Transforms Fishing Livelihoods in Car Nicobar